The Bonnet Carre Spillway has been opened more than a dozen times since it was constructed nearly 100 years ago, but the protection it offers New Orleans' levee system comes at a cost: The rush of fresh water into surrounding brackish estuaries can harm the species living there, sometimes killing off entire fisheries and reefs.Ěý

As the Mississippi River continues to rise, forecasters say another opening this year is , news that hasn't been welcomed by all on the Gulf Coast.

A critical engineering feat of its time, it's hard to imagine where New Orleans would be today without the spillway. But despite all the good it has done, many in south Louisiana have a complicated relationship with the long-standing structure — one that both saves and hurts so much.Ěý

A history of the spillway

The need for something like the spillway became evident after  when months of heavy rain across the South inundated the Mississippi River in seven states and displaced hundreds of thousands of Americans.Ěý

A man carries a load of bananas from a submerged wagon at Dupre and Baudin streets in Mid-City in mid-April 1927.Ěý

As the river swelled, Louisiana officials grew increasingly concerned that the levee system protecting New Orleans could break, flooding the city and causing potentially catastrophic damage.

To spare the Crescent City, officials took drastic and controversial action: In April 1927, dynamite was used to break a levee downstream from New Orleans in Caernarvon, sending floodwaters rushing into St. Bernard and Plaquemines parishes and displacing roughly 10,000 people.Ěý

Dynamite explodes to widen the gap in the Mississippi River at Caernarvon in 1927 and relieve the threat of flooding upriver in New Orleans.

As a direct result of the flood, U.S. Congress passed the Jones-Reid Flood Control Act of 1928, which federalized flood protection along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, with oversight from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.Ěý

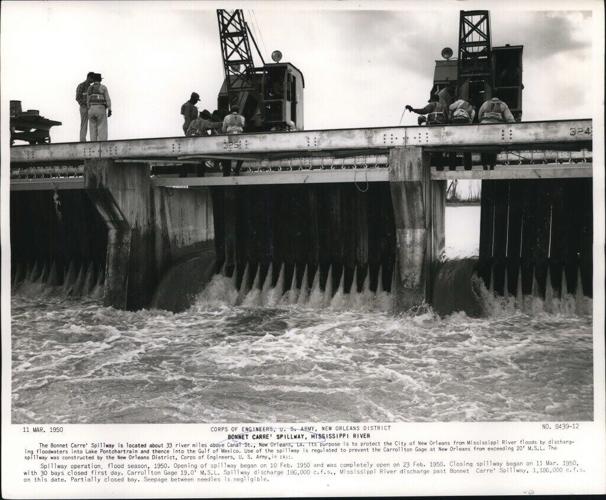

The Army Corps initiated its first surveys for the Bonnet Carre Spillway in 1928. Matt Roe, a spokesperson for the Corps, said the site where the spillway stands today was selected because the river had formed a natural crevasse there in floods that occurred before the levees were built.Ěý

Construction on the spillway started a year later and was completed in 1931, and highway and railroad crossings were finished in 1936, according to the Army Corps.Ěý

Bonnet Carre Spillway Bridges under construction in 1934.Ěý(NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune archive)

Dock and Levee board officials shown aboard the Dock Board yacht inspect the Lake Pontchartrain end of the Bonnet Carre Spillway in 1937. From left to right: Captain H. C. Whiteman, Mrs. Aion King, J. A. Thomas, Levee board president pro-tem; John Fush and Charles Donner, Levee board secretary, with telescope to his eye; L. B. Rennyson, behind Mr. Donner; Armand Willoz, R. J. Dreuding and James Wilkinson.Ěý

How it worksÂ

Now nearly a century old, Roe said the structure still works the same way it did when it was first built.Ěý

Composed of 350 "bays" that run alongside a 5.7-mile stretch of the Mississippi River about 33 miles upriver from New Orleans, Roe said officials open the spillway when the river's water levels are too high, an effort to relieve pressure on the levee system.Ěý

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers test opening the Bonnet CarrĹ˝ Spillway in Norco, La., as the Mississippi River nears flood stage, Monday, April 21, 2025. The test was for possible later opening if conditions warrant. It would be first spillway opening since 2020. (Staff Photo by David Grunfeld, The Times-Picayune)

Officials generally open the spillway when the river flow rate hits 1.25 million cubic feet per second, which usually corresponds to a river level of around 17 feet on the Carrollton gauge in New Orleans, or around 17 feet above sea level, according to the Army Corps.Ěý

To open the spillway, crews individually pull timber beams, called needles, from the structure's bays. Each bay contains around 20 needles, and each needle weighs around 600 pounds, according to the Army Corps.Ěý

Small gaps between the needles allow some water to flow through the structure at all times, Roe said. But when the needles are pulled and an entire bay is opened, fresh water from the river rushes through the spillway and into Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Borgne, and, sometimes, as far as the Mississippi Sound, all bodies of water that contain a mixture of fresh and salt water.Ěý

The amount of water diverted from the river — and intensity of impacts to wildlife in surrounding waterways — depends largely on how many bays are opened and for how long, Roe said.

The Corps is currently engaged in looking at the best ways to manage the Mississippi River and, in part, how to better operate the spillway.

The last time all 350 bays were opened was in 2011, but the longest duration opening was in 2019, when the structure was partially open for a whopping total of 123 days.Ěý

'Like opening a firehose'

The Bonnet Carre Spillway has been opened 15 times in the more than 90 years since it was built, but 2019 is the year wildlife and commercial fishing groups always talk about.Ěý

After intense rains in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys, the spillway had to be opened twice that year, killing off oyster reefs and other animals in neighboring waterways. .Ěý

John Fallon, director of sustainability and coastal conservation initiatives at Audubon Nature Institute, said there were more than 300 bottlenose dolphin deaths reported in the northern Gulf of Mexico that year. released by federal researchers found that many dolphin carcasses exhibited signs of exposure to high concentrations of fresh water, including skin lesions, "resulting from extreme freshwater discharge from watersheds that drain into the northern Gulf of Mexico."Â

Brackish bodies of water contain a mixture of salt and fresh water, and Fallon said the organisms that have evolved to live in those waters can handle fairly significant flocculation in salt concentrations.

But when large portions of the spillway are opened for a long time, Fallon said, it's a different story.Ěý

“It’s when we force that much freshwater directed through a single channel like that — it’s like a firehose."

Most organisms can't handle that kind of instant, drastic change, and Fallon said those most severely impacted are often animals like oysters, clams and other bottom feeders that can't get up and swim away.

University of Mississippi environmental toxicology master’s program graduates James Gledhill (left), and Ann Fairly Barnett examine dead oysters they pulled from the Mississippi Sound with an oyster dredge. Oyster mortality in the sound increased in late 2019 after the Bonnet Carre Spillway and rivers along the Mississippi coast added too much freshwater. (Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services)

The difficulties come down to their very biology, he said.Ěý

“It would be like if you’re breathing air but we changed the composition of the air," he said. "You’re going to struggle.”

Finding balance

It all comes down to ion balance, according to Cassie Glaspie, an assistant professor in the Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences at ÂŇÂ×ÉçÇř. Salts are composed of ions, and Glaspie said freshwater marine species have evolved ways to keep more ions in their bodies, while saltwater species have found ways to rid their bodies of excess ions.Ěý

Some sea birds, for example, excrete excess salt through glands on their bills. Sea turtles can expel salt by crying, Glaspie said, and many saltwater species have extremely salty urine.Ěý

The marine species that live in Lake Pontchartrain and other brackish bodies of water are really just saltwater species that have evolved to become highly tolerant to fresh water, Glaspie said. That means they're good at handling a lot of variability.Ěý

But an extensive spillway opening can swamp those abilities.

“These types of management decisions are outside the realm of normal," she said.Ěý

It's not just the inundation of fresh water, Glaspie said. The Mississippi River is also significantly cooler and nutrient-dense than the surrounding shallow estuaries, leading to drastic changes the temperature and water quality.Ěý

The organisms that struggle most are, concerningly, also those that support the rest of the food web.

Rangia cuneata, a kind of web clam, are almost always found in tissue samples taken from the bottom of Lake Bourne, Glaspie said, meaning they support and feed much of the other life found there. Those clams are especially vulnerable to drastic changes. That's bad news for all the animals that feed on those clams.

Yet, Glaspie remains hopeful. She's seen coastal species in the area nearly entirely wiped out by all kinds of crises: hurricanes, floods, a recent drought. They always find a way to rebound — and fast.Ěý

"The communities we have here are very resilient to that, because they have to be to live here," Glaspie said. "Much like the people who live here.”Â